G: The Taliban do not have a good reputation for respecting women's rights, as we in the West would understand them. Have you been able to approach and speak with any women?

B: In some rare instances, but not in Kandahar. That's impossible.

G: How come?

B: Even if you do see a woman in the streets, in Kandahar,which is rare, the women in the streets are almost not supposed to be seen. That is one of the effects of the Burqua that they all wear. So it's really difficult to communicate with women. I can only think of one woman I met there, and she was an aid worker with a non-profit that I was involved with. The Taliban have made the isolation of women worse, but they are following hundreds of years of tradition which have created an extreme isolation of men from women. From childhood on, Pashtun boys and girls are almost completely separated, even brothers and sisters. If a woman wants to leave her husband because he has been too violent, the person she has to fear the most is her own brother.

G: Fear? She fears her brother?

B: Yes, he might kill her. It is his job to kill her for leaving her husband. Because by leaving she has maybe saved her life, but she has insulted her own family name. The family name in Pashtun culture is everything. By the Pashtun code, an insult must be resolved by payment. In the tribal areas, where foreigners are not normally allowed, each home is basically a walled compound, with walls 24 inches thick, and in the center of the compound is a tower with a rocket-launcher at the top. And they will fire rockets at the compounds of other families with whom they have an ongoing dispute. And who knows what started the dispute? Just like two Sicilian families. It's the same thing -- lives lost on both sides, but what was the original grievance? Nobody remembers. Yes they are very vengeful and they are very unlikely to let it go. And, anyway, although their culture is very repressive towards women, from their own point of view, the Pashtun men also revere their women. This is what makes this culture complex.

G: As a foreigner, were you ever caught up in that complexity?

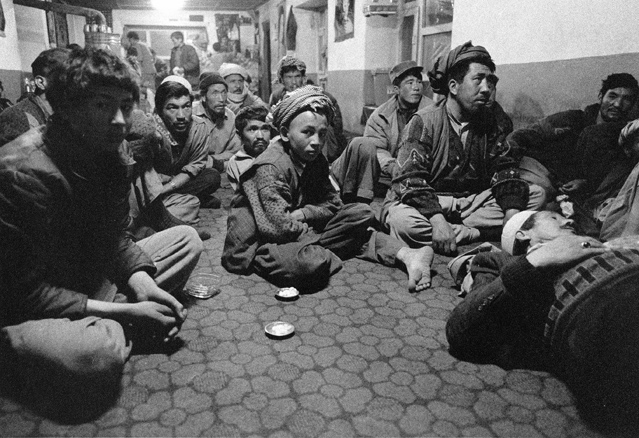

A 12-year-old boy and several adult refugees from the Hazara ethnic group, sit on the floor of a restaurant where they will spend the night (Bamian, Afghanistan, 2004).

Photo by Beb C. Reynol from Forced Destiny

B: I did insult someone once. I was on my way from Islamabad to Peshawar on public transport. There were about 20 people, and I was in back; and with me in back were a bunch of young Pashtun who were trying to tell me about their culture. It was my first visit. And suddenly this man on my left points to a car caravan of a wedding. So I put my head out the window and whistled as loud and long as I could to celebrate the wedding. Everyone in the bus turned around and it was the first time I learned whistling is extremely impolite in Pashtun -- especially in the presence of women. If you have any women near you, do not whistle, or if you do, run for your life. But they did realize I was a foreigner and I didn't know anything about it, so they left me alone.

G: You mentioned working with a non-profit organization while in Afghanistan. What kind of work did you do?

B: Well, two different times I was training local photojournalists at Aina Photojournalism Institute, which is an organization focused on providing media training and building the dilapidated media/press industry in Afghanistan.

G: You were training the local people to do the same kind of thing that you do?

B: We had at the time an anti-child labor marketing project that was launched by UNICEF. So I was helping the photographers to edit their work, and teaching them how to create stories.

Hazara children in an orphanage (Kabul, Afghanistan, 2004).

Photo by Beb C. Reynol from Forced Destiny

G: Were you helping them tell stories about child labor?

B: Yeah, for example, we went to some of the orphanages that were keeping kids of the ethnic group called Hazaras, who are supposedly the descendants of the Mongolian Army from 1000 years ago. They are the true minority of ethnic groups in Afghanistan and are the subject of a tremendous amount of persecution by the Taliban.

G: So your photojournalism students are from other ethnic groups, documenting the Hazaras?

B: They were were probably a mixture of Tajik, Ismaeli, and some Hazaras, but actually, to be honest, I cannot be exactly certain of the ethnicities of my students because, during that time, in 2003 when I came to Kabul, it was not okay to ask someone's ethnic group. There was too much tension because of the way the Taliban favored the Pashtun.

G: So it sounds like the ethnic rivalry that you witness, which was very present but could not be spoken about directly, gave rise to your current project of allowing people to co-create photographic portraits of themselves, literally showcasing their own identities and telling their own stories.

B: Yes. The power of the silent, untold stories gripped me. Because, another thing that was not OK to talk about was the very topic of the project: child labor. You see, it was not like the country was forcing these kids to work, but because the war -- which had lasted at the time more than 23 years in 2003 -- had decimated so many males that the family situation was transformed. A lot of kids were becoming the head of the family or providing for the family. So it was very difficult at that time for even an organization like UNICEF to describe these things as child labor.